Voice of the Customer / VOC

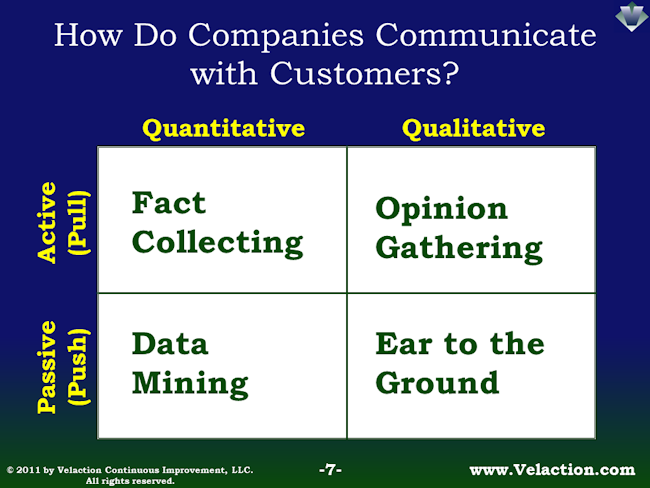

The “Voice of the Customer” (VOC) is the collective information that an organization obtains from or about its customers. This information comes in one of four basic ways, as shown on the image below:

Organizations can either actively request information from a customer or can seek out information that is already flowing on its own. Likewise, the information can be either highly quantitative, as with sales figures, or can be qualitative opinions.

The primary purpose of listening to the voice of the customer is to gain a clear understanding of the customer’s wants and needs, and then to translate those requirements into a plan of action.

Another significant benefit of paying attention to the voice of the customer is to actually determine who the customer is. On occasion, a company might realize that the organization is missing the mark on who they are really serving. More commonly, though, diving into the VOC will show logical splits about where customers should be segmented. Treating different types of customers the same generally results in all of them being unhappy. But cater product offerings to specific groups of customers, and you will have a much better chance of delighting them.

Keep in mind that this approach to learning about customers is not limited to just external customers. It is also highly relevant to how internal customers are handled. Be careful when catering to internal customers, though. If they are not acting in the best interests of the external customer, you may be delighting your coworkers at the expense of the people actually paying the bills.

The average frontline employee practicing continuous improvement will, in all likelihood, not be a driver of a VOC data collection effort. More commonly, they will be a recipient of VOC information collected by other people who specialize in assessing the needs of external customers.

They will, however, occasionally be asked to offer up their observations or participate in data collection efforts driven by the marketing team.

Despite this insulation from the nuts and bolts of the voice of the customer for the average Lean practitioner, it is important to understand how the company goes about gathering knowledge about its customers. And it is also important to know how to use VOC information to make customer-facing decisions.

Sources of Voice of the Customer Data

Let’s start by looking at the sources of VOC data that the company is likely using.

Fact Collection

- Customer surveys

- Online polls

- Online data/customer profiles

- Industry data/benchmarking

- Market research

- Competitive research/business intelligence

- Customer research (policies, website, customer publications, etc.)

- Product response cards

- Customer observation

- Product testing

Opinion Gathering

- Customer surveys

- Online polls

- Exit interviews

- Customer interviews

- “Day in the life”/ride alongs

- Focus groups

- Product response cards

- Company blog/forums

- Customer observation

- Product testing

Data Mining

- Warranty info

- Service calls

- Technical support data

- Call center data

- Product sales data/sales cycles

- Demographic information

- Point of sale (POS) data

Ear to the Ground

- Blog watch

- Internet searches

- News reports/stories

- Employee reports on customer interactions

- Customer complaints and praise (unsolicited)

As you may notice, many of the methods listed above can take years of focused training and experience to master. Typically, because of the risk, most employees are not asked to take on external customer facing VOC tasks as part of regular continuous improvement efforts.

For example, line managers dealing with a quality problem at an auto manufacturer would probably not arrange a customer focus group, but they would certainly try to act in accordance with the company’s view on what customers want.

That is possible because sophisticated companies combine the VOC from all the different sources into a concise list of requirements about the customer segments that they serve. And they make sure that those needs are communicated throughout the company and that day-to-day operations take those customer requirements into account.

The High-Level View of the Voice of the Customer Process

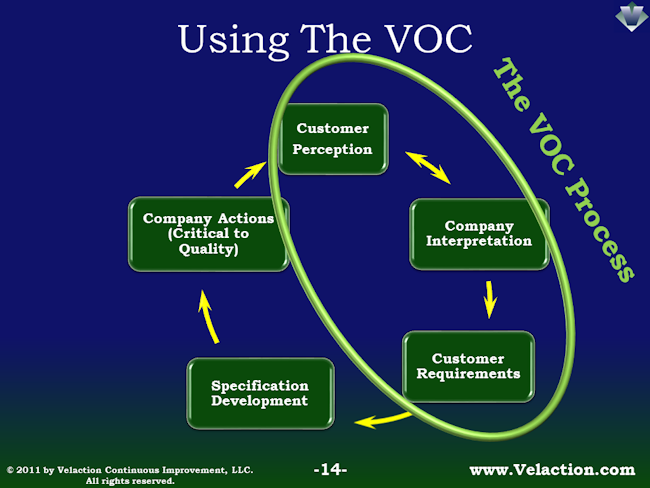

The high-level voice of the customer process is relatively simple. Obviously, the actual data gathering can be complicated, but the overall intent of VOC is easy to grasp. The company opens a channel of communication with the customer and tries to get an accurate interpretation of the customer’s perception about their needs, desires, and the performance of the company.

The company takes the information it collects and distills it down into a set of customer requirements, which, in turn, end up as product specifications or service standards. These specs then drive the company’s behavior.

Ultimately, the company’s actions close the loop and start the cycle all over again. Every behavior by the company is watched by the customer.

If you are a marketer, you may be actively involved in planning this VOC loop. But most people doing continuous improvement on a day-to-day basis are not. They operate primarily in the “Company Actions” area.

The metrics that drive their improvement plans, for example, are the results of the VOC effort. And the way that teams act to meet their targets determines how the customer will perceive the company in the future.

Internal Customers

When the focus on the customer turns from external to internal, frontline employees and leaders are on their own in developing the VOC that will clarify how to best serve their coworkers.

There are four basic challenges when trying to gain a deeper understanding of how to meet internal customers’ needs.

- Most people operating within a group that serves internal customers have neither the expertise needed to gather VOC data, nor do they have the resources to do so.

- The concept of value is often moot when dealing with internal customers, as there is nothing to trade for what they are asking for.

- The customer and supplier are often measured on opposing metrics. Improving one for the customer can lower one for the supplier. This leads to local optimization.

- There is no competition. External suppliers must battle to keep their customers. Internal suppliers have a tendency to get complacent because their customers can’t leave.

The first point is relatively easy to understand. If you have never conducted a focus group or learned about how to mine data from a database, or developed a customer survey, it is hard to do so effectively.

The second point is more subtle. With external customers, it all really comes down to money. For example, customers may clamor about losing meals on flights, but they flock to the low-cost carriers that don’t provide them. Or they may complain about long lead times, but choose the cheapest, slowest shipping options. When it comes right down to it, customers primarily show what they really value with their spending patterns. Of course, the voice of the customer data helps make the decisions that drive spending behaviors, but the “Check” step of PDCA generally focuses on whether sales went up or not.

For internal customers, though, there is no invoice. So, internal customer can ask for everything, and never have to prove that the value they get from the activity outweighs the costs to deliver that service. It is even more complicated when the costs are borne by the supplier, and the benefit is felt by the customer.

That concept leads to point number 3 above. Each organization in the company likely has its own metrics. Each manager is also likely responsible for meeting budgetary requirements. So, imagine the potential for conflict when, for example, the customer process’s manager can save some money, but it will add to the costs borne by the supplier process. It is easy to see how this sets up the potential for conflict.

The last point comes from a conversation I had with a Japanese consultant years ago in my Lean infancy. He asked why we let our internal suppliers treat us worse than our external suppliers did. He said we were on the same team, so we should be treating each other at least as good as we treat the end customers.

Value Stream Thinking

The most effective way to begin resolving this potential conflict is to start from a unified position. Generally, this entails taking a flight up to 30,000 feet and looking at the whole flow of value from an external customer’s perspective and seeing what each process does to contribute to the entire values stream.

This is one of the reasons that it is important to have a value stream manager that oversees the entire series of processes from initiation to completion. When there is a need to reallocate resources, or to adjust metrics upward and downwards as work is rebalanced, a value stream manager wants the best global results. He or she sees the benefit of spending 5 extra minutes doing something in one area to save 20 minutes somewhere else. When organizations are set up in a functional manner, applying the voice of the internal customer can be inhibited by boundaries. Many managers act in a way that preserves benefits for their own team, even if it increases costs in other areas.

Of course, not all organizations are set up with value stream leaders, and even those that are will still have areas where work crosses leadership boundaries. Acting on voice of the customer data in those cases can be particularly challenging.

Internal Customer VOC

Every organization is different and will have its own unique set of requirements. No step-by step approach will work perfectly in all situations. That said, the framework provided below can help you organize a plan on how to better understand the true needs of your internal customers and separate out the “nice-to-haves” that cost a bit too much.

One thing to keep in mind before you get started: You need to strike the balance between the amount of effort you spend on nailing the VOC, and the benefit you will get from having near perfect information versus pretty good information. There is often an inflection point after which the costs go up more than the benefit does. When millions of dollars of sales are at stake and the competitive sharks are circling, you’ve absolutely got to get the external VOC right from the start.

With internal customers, you still want to get the VOC right, but you are operating under a different cost-benefit framework. For a small process you might only save a few thousand dollars in a year. You probably won’t be bringing in a focus group expert to meet with Sally in accounting for 3 days. So, as you follow these steps, keep the projected gains in mind.

- Review the value stream. As mentioned above, take a high level look at where the process in question fits into the big picture. Look specifically at how it affects external customers, and what the risks of process failure are.

- Define the customer. Early on in any internal customer VOC effort is to define who the customer actually is. This is an iterative approach that you will adjust as the needs of your customer segments become clearer in later steps. But you have to start somewhere. Be specific about who the customer is. If it is a person in a particular role, define that rather than just mentioning an organization. For example, specify “field sales engineers” vs. “sales” and “manufacturing cell supervisors” vs. “manufacturing”.

- Do a SIPOC analysis. Going through this step helps keep you from missing important pieces in the analysis of a process. It will also highlight situations where a customer is also the supplier. It is not uncommon in support or administrative processes for parties to have multiple roles. An operations manager, for example may see the facilities team as a supplier when setting up a new workstation. The facilities team may see that same ops manager as the supplier, responsible for providing the materials and any specialized equipment that needs to be installed.

- Open a VOC dialog with the customer. Let the internal customer know you are starting the voice of the customer process. Identify a representative who can speak for the group and open a feedback channel. Don’t surprise people down the road. Forge a partnership early on.

- Ask what the customer needs from you. As mentioned earlier, you will need to balance the needs to get good VOC information with the benefit you will get in having that information. A good place to start out is to just ask the customer what he or she expects of you. It is surprising how often this simple step has never been done.

- Ask what the customer thinks would be nice to have from you. Make a distinction between the absolute essentials, and the nice-to-have things. Just by framing the question this way, you’ll get the customer thinking. Finish this step by having the customer rank order all the things that they want from their supplier. Go a step further and ask the customer to allocate a limited number of points to all of the requirements. A good rule of thumb is to give about triple the number of points as there are items on the list. You are looking for an initial read on what the customer finds most important.

- Review existing information. Think through all the sources of information that already exist about your customers. Phone call history, emails, any recorded quality problems, demand patterns, etc. all provide good information. Bounce the facts you uncover against the initial customer comments about their needs and wants. If they are in alignment, you probably are on track for setting up initial metrics in step 9. If not, go to step 8.

- Gather more information. If there are still questions after your initial discussion and data review efforts, you’ll have to come up with a voice of the customer plan. This will include, among other things, surveys, observations, process analysis, and data collection on quality, complaints and demand. Generally, simple is better. The more detailed a survey is, the less likely it will be filled out. Focus on the critical gaps in your information. If you are not comfortable with this step, seek out some expertise from within your company. Many people in marketing will have experience in uncovering hidden needs.

- Develop initial metrics. One of the benefits of the internal customer-supplier relationship is that there is generally more of an opportunity for the PDCA cycle to operate. When you get it wrong with an external customer, you often don’t get a second chance. With an internal customer, you can use feedback about failures to continue to improve. As you begin developing metrics, you should have enough information to at least decide on what to measure, even if there is not yet agreement on “how much” yet. Settle on some metrics and start tracking them. Leave the goals off at this point until you establish a baseline. Don’t forget to include metrics to measure the internal customer as well. It is important to know how good they are at providing the information needed to help them. If they are chronically “late” (probably not yet defined), then track how far in advance they place requests.

- Review the initial metrics. Once a baseline is established, get back together with the customer, and set targets. Continuous improvement will play a major role here. As a supplier, you will have to commit to improvements to close the gap to what the customer wants. The customer, though, will have to also look at his processes and make sure that they are working to improve as well. Again, unlike in an external relationship, the ultimate goals within the same company are aligned. If there is a dispute about how aggressively to set improvement targets, use a decision matrix with the value stream manager or a mentor moderating. It will take big concepts and break them down into small, manageable discussions.

- Establish targets on the revised metrics. Lock in the metrics, complete with improvement targets. Add them to your monthly operations review.

- Act on the VOC driven metrics. Develop a plan to reach your goals. Use countermeasures to close any gaps. Put the PDCA cycle through its paces. The ultimate goal is to create processes that consistently deliver on the needs and wants defined by the voice of the customer. That bears repeating. The only way to continue to improve in the eyes of the customer is to create robust processes.

- Maintain communication. Talk to the customer as you make progress or run into obstacles. Recruit the customer to help solve those problems. Keeping a channel open goes a long way toward maintaining an effective working relationship, especially if the customer can see progress and a plan.

- Continue tracking VOC. Like the external customer VOC model, never stop gathering info. Record complaints, and periodically go back and watch your customers in action to make sure the situation is not changing.

- Retire obsolete metrics. When a VOC target is stabilized and no longer needed, retire it. You should still consider keeping any metrics that are critical to quality, though. It will help you catch problems early. But remember that there is a cost to monitoring information. If a new and improved process fixes a problem, you won’t need to keep tracking it.

![]()

Play a sample…

Voice of the Customer Words of Warning:

- Don’t forget to factor continuous improvement into the future state plan. The capabilities of an internal supplier should not be static. Put an aggressive plan together to meet demanding requirements instead of just rejecting them. Use the estimated future costs in any cost-benefit analysis, and then work to meet those cost targets.

- The best external customer relationships are ones where both sides win, but the truth is, one side nearly always wins just a little more than the other one. It is, by nature, a cooperative and competitive relationship at the same time. Suppliers always want to make a little more, and customers always want a little more for their money. Internal customers, however, are more aligned with their suppliers than external customers are. Don’t forget to overtly state the company goals when talking about internal voice of the customer. It will remind both sides of the relationship that they are on the same side.

- The supplier and customer hats can be interchangeable. Consider marketing and inside sales. The inside sales team might execute a promotion, acting as a supplier to the marketing team, but the marketing team may need to provide proper documentation, arrange for promotional materials, etc. That makes the marketing team a supplier as well.

- Don’t overdo gathering internal voice of the customer information when the improvement opportunities don’t justify it. Continuous improvement is, in large part, about prioritization. You will always have a long list of improvements to make. If you spend too much time on VOC, you will never get around to making improvements. But…

- Don’t act without solid information. Far too often “improvements” are made without a clear understanding of a process or of the needs of the customer. Those efforts seldom pay off as much as they could with more time spent in the ‘P’ step of the Deming cycle.

- Be careful about making assumptions about customers. You really don’t know what they want unless you ask. As a Lean consultant, I often hear people reject ideas because “The customer will never go for that.” In most cases, they never asked the customer.

- Internal relationships are dependent upon the corporate culture. With a good continuous improvement mentality, the focus on goal setting syncs nicely with VOC. Without it, and with no value stream vision, the conflict can be significant.

- Keep the ‘WIFM’ principle (“What’s In It For Me?”) in mind when discussing VOC with team members. When customers are happier, they tend to complain less, making employees happier.

You are the eyes and ears of the company, and as such, you have the best opportunity to identify customer needs. This is especially true for those of you with customer facing jobs.

Try to read between the lines on what the customer is saying. If they comment on the music while they are on hold, they may really be saying that they feel like they were waiting on the phone for too long.

Also keep in mind that as your company becomes more customer-centric, you’ll be asked to do more things. Whether it is actual work for the customer, or supporting work like data collection, try to be accommodating. But also make sure that your boss is not just adding work. Discuss the process and ask the hard questions about capacity. If you are asked to do more, you’ll need help. That may come in the form of more manpower, or it may be improvement support. Either way, though, your boss should show you respect and make sure he or she has a plan on how you will handle the additional responsibilities.

One of the problems with leaders is that they are often the victims of their own success. They have “made it” and tend to feel that their experience and expertise have been validated by their promotion. As a result, they tend to act in the absence of facts and data.

Get in the habit of doing a voice of the customer exercise for each process you oversee and translate the results of that exercise into operational metrics.

Key Points About the Voice of the Customer:

- Internal voice of the customer is significantly different from external voice of the customer. The primary difference is that internal customers don’t speak with their wallets, so they prioritize less than external customers do.

- The voice of the customer is the composite of all the different ways a customer communicates with your company, whether actively or passively.

![]()

Pick a simple process where you have run into some conflict between internal customers and suppliers. Go through the basic process listed above to develop an agreement on new metrics to monitor the performance of your process.

Find a mentor to help guide you through the process. An expert on VOC is preferred, but most companies have a shortage of significant voice of the customer experience. In that case, a strong problem solver can still ask hard questions and challenge your thinking to get better results. The key is to have an impartial third party to help guide you to act in a way that is best for the company, not just for your department.

![]()

Available forms and tools to support VOC:

- The SIPOC Analysis Sheet (get a free version) can help organize your review of what your process provides to your customer.

- The KPI Bowler is useful for tracking VOC related metrics.

- You will make ample use of Countermeasure Sheets as you attempt to close the gap from where you are and what your customer wants.

- The Decision Matrix Template is an effective tool for negotiating where to set targets.

0 Comments