Kanban

A kanban is a signal that gives an instruction to get, move, produce, order, or take some other activity with production materials. Its literal translation from the original Japanese term, though, is “signboard” or “billboard”. Kanbans tell you when to order, what to order, how much to order, and where to order it from.

The ordering, though, is not necessarily from an external supplier. It may also be from an upstream process or some other department within your own company. It may even be an order from a warehouse. You will often hear the words kanban system, kanban, and kanban card, used somewhat interchangeably.

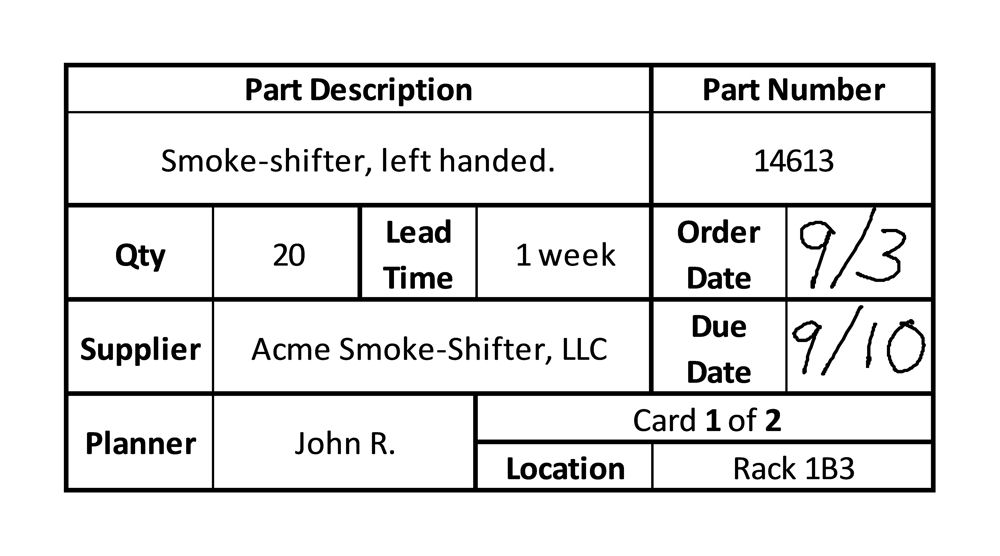

This sample shows some of the information you will likely see on a kanban card.

While the term kanban technically refers to the card, in practice, it is often used to describe the materials governed by the card.

The kanban concept is versatile, and can be applied in many variations both on the shop floor and in the lean office.

A kanban may be a location on a floor, a cart, a pallet, or anything else you can think of that conveys a message about what to do regarding the materials.

A kanban tells…

- An upstream operator to produce more parts (production kanban)

- A material handler or water strider (to pull parts from another location (withdrawal or transport kanban)

- A purchasing group to buy more material (purchase kanban)

A kanban system is one of the key ingredients to transitioning to pull and to the implementation of Standard Work. It is worth noting that kanban systems, due to the tight linking to standard processes, work best with high quality, low variation parts and materials.

Kanbans rely heavily on standardization and 5S to operate effectively.

Watch Our Kanban Overview Video

Watch Our Kanban Overview Video

You are probably already familiar with the underlying concept of kanban, even if you can’t recite its definition or if you don’t know it by that name. In all likelihood, you have a kanban system in your home. Dig down in your box of blank checks from your bank and find your last checkbook. On the front of it you will see a close approximation to a kanban card. That piece of paper with the reorder information on it is essentially the same as a kanban card used by your company. The main difference between that reorder slip and the kanban card, though, is that the former does not have as tight of a link to your actual usage of checks, nor does it factor in the procurement time it takes to receive the new checks.

So, think about how the check process works. As you get towards the end of your box of checks you tear off the reorder form and drop it in the mail. Granted, many banks are transitioning to an online ordering system, but the principle is the same. The paper (kanban card) signals an action to purchase more.

So, what, exactly, are kanbans supposed to do? Kanbans act to control inventory levels and to make replenishment systems more visual. But be careful about one incorrect assumption that people frequently make about kanbans:

Kanbans do not reduce inventory.

A common misconception is that using kanban will reduce inventory. Not true. All kanban does is provide a simple and effective way to manage materials.

Kanbans tell you when to order, what to order, how much to order, and where to order it from.

If the amount that the kanban tells you to order is set too high, you will be sitting on a lot of excess. If it is set too low, you will run out.

Let’s go back to that checkbook example. If the reorder sheet said to order ten thousand checks, you’d have way too many—even though it was ordered with a kanban. If the order form requisitioned only three checks, you’d probably run out very quickly.

So, kanban just puts the structure in place to manage the reordering process, whether from an internal warehouse or upstream process, or from an external supplier.

So, how do you calculate the right quantity for the kanban? The answer to that can be rather complicated. Some companies use a sophisticated kanban calculator. It might include some advanced statistics, required service levels, and a bunch of other data. Other calculators are a little less complicated. They might use more estimates and less hard data.

More advanced calculators can bring inventory down effectively, but they require accurate data—and lots of it—to work well. Sometimes the cost of this complexity outweighs the benefit. While determining a kanban quantity from a formula is all science, there is a bit of art involved in picking the parameters for the formula.

Sometimes, though, rough estimates are made according to general data, and then the levels are tweaked through trial and error to adjust the necessary safety stock to cover variations in demand, lead time, and other factors. In a nutshell, for a two-bin system, the quantity is the demand during the lead time, plus a safety stock. This assumes you drop cards when the bin is empty.

NOTE: Some systems require that you drop a card as soon as you take the first item. (“Break the bin, turn it in”) Some systems have you drop the card when you empty the bin. Both have advantages and disadvantages regarding convenience, number of open orders, and the average amount of inventory on hand.

Regardless of how advanced a calculator is, the goal is the same. When a kanban card is “dropped” (the slang for depositing the card in a kanban post—the collection point) the remaining parts must keep the production process going until the order is filled.

So, what might affect the quantity that needs to be on hand?

The most important factor is knowing how much of your product your customers are actually buying. Setting up kanban can be a challenge if demand fluctuates wildly.

- Internal Processing Time

The time from when the card is “dropped” until the order is placed.

- Supplier lead time.

The time it takes to get the order filled. Obviously, the longer the lead time, the greater the quantity needed.

- Minimum order quantity.

You might want a smaller amount, but your supplier has a policy that requires you to order in larger quantities. This is generally because of an inefficient ordering process. You may end up with more than you want for this reason. (Side note: Some companies deal with this issue by using uneven kanban quantities or a reorder point, but that’s beyond the scope of this article.)

- Pack-out size.

For example, eggs generally come by the dozen. You might need 33 but have to order 36—a multiple of a dozen.

- Supplier reliability.

If a supplier can’t deliver on time, or frequently mixes up orders, the kanban quantity must go up—at least until you find a better supplier or convince your current one to improve.

- Product quality.

If parts often don’t work right, you need more in the bins to account for the scrap rate. Again…only until the supplier improves quality or is replaced.

Information Contained on Kanban Cards

- Supplier

- Card number and total number of cards

- Product info, including SKUs with barcode, name, pack quantity, etc.

- Kanban quantity

- Material location

- Date ordered

- Lead time

- Date due

- Parts usage

The most basic form of kanban is the two-bin system. As the name implies, this method of resupply uses two bins. One is normally somewhere in the fulfillment process, and the other is sitting with the materials in the production area. There is generally a little bit of overlap—due to the existence of safety stock. This is the little bit extra to cover the variation in the resupply process. Obviously, you want as little safety stock as you can get away with.

This is where the biggest difference in the calculators is seen. For simple calculators, it is like leaving for work 5 minutes early every day. You just pop in a little extra with each bin. For advanced calculators, the math takes into account standard deviations and statistics and your expected service level—a measure of how often you run out of parts. You might be able to get that five minutes early to work down to 3:47. Doesn’t sound like much of a gain regarding coming to work on time, but when you multiply it out by all the different part numbers in a factory, the savings can really add up.

When parts get expensive or have very long lead times, you might see more than two bins. Instead of being in a supplier’s production queue at one spot for thirty parts, you might have three orders for ten parts each in various stages of the ordering process. One might be somewhere in the internal ordering process, one could be at the supplier’s production area, and the last one might be on the UPS truck. Plus, you’d have a fourth card in your own production area. Obviously, the card is not really in those places—just the parts that the card matches up to.

Think of it like a merry-go-round. If you stand in one spot, the horses file past you. If it had only two horses, each one would have to carry a big load. Add in two more horses, and their loads are cut in half. Multi-card kanban systems are more complicated, and far more prone to errors and lost cards than two-bin systems are, but they do help reduce inventory in some cases.

A common variation of the multi-bin kanban system example is when an empty rack is a signal to move a component through a fabrication process. I frequently use Go-Karts as an example. In my fictitious company, we have a rack for each Go-Kart chassis. The empty rack is a kanban that assembly sends back to fabrication to signal them to produce another one. The racks wind their way through the whole production process. In this configuration, you are not likely to see two-bin systems. More often than not, you will see many carts each holding one item.

Kanban vs. Computers

So, why kanban and not a computer system? Because it is visual. It is easy to miss something on a computer report. It is hard to walk into a production cell and not notice that a bin is empty, or that a card is missing. Problems become immediately apparent. Of course, many kanban systems link into a computer system—a purchaser may just scan a barcode to place an order. But the visual management at the point of use for a kanban is hard to beat.

Plus, operators can be trained to review parts levels in their area. If they notice that both bins are nearly always full, they can point out an opportunity to reduce inventory. If the safety stock is nearly used up with each kanban cycle, they can see that the inventory is set too low.

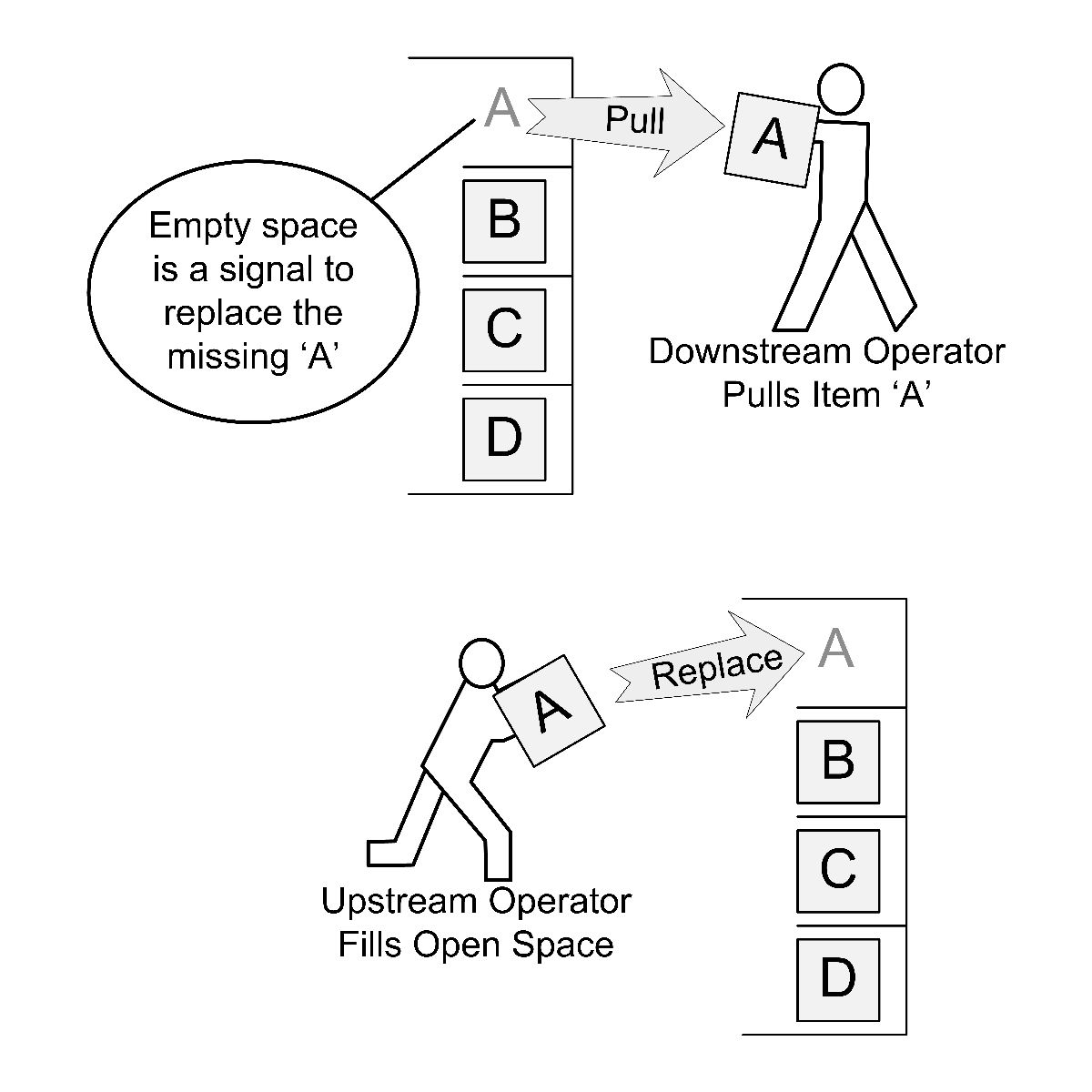

In addition to the multi-kanban system, there is also a specialized type of kanban called a supermarket. This is generally used on mixed model lines. There are a set number of items stored in designated spots. When the downstream process pulls an item, a kanban card or the empty space signals to the upstream process what to build next. The quantities of each type of item are dictated by the model mix. It can be confusing to manage productivity for upstream processes using this type of system when the items come from different areas.

Supermarket Pull Process

Kanban systems often have rules to make sure that they work effectively. (Taiichi Ohno had six rules for kanban use. We have built off of this for 8 rules.)

Sample Kanban rules

- No production without a kanban signal

- Only produce the quantity indicated on the kanban

- Treat kanban cards as controlled items

- Only pull from one kanban at a time

- Downstream process signals the upstream process

- Materials must have a kanban attached to them

- Process the kanbans in sequence (no cherry picking)

- Only send quality materials

Kanban Prerequisites

- 5S

- Standard Work

- Reliable suppliers

Two things to keep in mind. The first is that kanban is a workaround for when flow is not possible. If flow was present, there would be no need to signal the upstream process.

The second is that kanban does not, by itself, reduce inventory. It manages inventory. In some cases, going from no system to a kanban system might even increase inventory (the quantity is based on kanban calculation). You will need to do things like improve quality, stabilize lead times, and reduce pack quantity to bring kanban sizes down.

As effective as kanban systems are for helping structure your inventory management efforts, there are some common pitfalls to avoid.

- Kanban systems require industrial discipline.

Kanban systems only work when teams follow the rules consistently. If rules are followed sporadically, there will almost certainly be parts shortages.

- Watch for abnormal conditions.

Material with no kanban card attached, cards lying around, and past due cards without any action are all abnormal conditions and indicators of problems.

- Don’t cheat the system.

People like to hedge. If there’s a secret stash, the kanban system won’t work to highlight problems.

- Don’t blame kanban for other problems.

Kanban systems work like beacons. When suppliers are unreliable, parts quality is poor, or lead times are too long, kanban systems make the problems very noticeable. Don’t discard the kanban system—fix the problems.

- Don’t stick with the same quantity forever.

When demand changes, the kanban quantities will have to change as well. For demand spikes a single special order, often called a “white card” can be placed. For permanent changes, the quantity should be adjusted. Microsoft Excel and Word work together nicely to print cards quickly (merge functions) when demand changes.

- Don’t limit your creativity.

Different style cards can signal different things. Triangle cards may be internal. Suppliers may be color-coded. Parts racks can themselves be kanbans. Use kaizen to improve the kanban process.

In kanban systems, your life tends to get easier. Switching to kanban can be a chore (lots of cutting and laminating and Velcro), and it can be unnerving to see your safety net of inventory go away, but most people soon see the benefit.

Once the system is in place, dropping cards for operators is a breeze. Many companies even have material handlers who come past all the work areas collecting cards and empty bins and replenishing materials. When this is done with a standard process, the person is known as a water strider or mizusumashi in Japanese.

The biggest hang-up people have is in maintaining the discipline to keep the system running effectively. It is easy to stick a card in your pocket and bring it home on accident. Or during crunch time, it is easy to grab from the second bin before you drop a card. Be careful. A kanban system, as robust as it can be, will fail if the process is ignored.

Lead by example. Walk through the work areas every day looking for problems with materials. Stress following the process. Make sure you don’t take a shortcut when time gets tight.

Focus on making the system visual so problems are immediately visible. When you transition to kanban, start with the highest value parts first (use an ABC inventory analysis). You’ll set yourself up for the biggest inventory reduction that way.

Key Points to Remember When Using Kanban:

- Kanbans are signals to take an action to get more material.

- By themselves, kanbans don’t reduce inventory. They need kaizen to go along with them to bring quantities down.

- Kanban systems require industrial discipline. Most companies have a set of kanban rules to follow.

![]()

Kanban systems can be confusing until you see them in action. If you are unfamiliar with them, try to find a local company that uses them, and arrange a tour. Many companies are willing to work with other local businesses to share best practices.

When you have a good idea of what a kanban process is supposed to look like, try to implement one of your own. Start out by trying to make a few cards in a single area and work out the kinks in your processes. Once you gain a better understanding and learn a little more how you want to run things in your own organization, it is time to stabilize the processes and start rolling them out in other work areas. I want to stress that point: document your processes and follow them! If you don’t, you’ll end up with several different kanban processes that won’t play nice together.

![]()

This term can be augmented with our kanban card generator. You can purchase it at Continuous Improvement Central, our training and resource center.

![]()

This term is part of our Kanban Overview module.

0 Comments