Opportunity Costs

Imagine that it is a Friday afternoon. The sun is shining, and you are looking forward to all that the weekend has to offer you. You only have two days off. What are you going to do with your time? You have the option to play—maybe a round of golf with some friends. You could knock something off your “to do” list and replace the grout in the shower. Or, maybe you just want to relax and catch a game.

If you head out to the links, you miss seeing your favorite team in action. If you do your chores, you miss out on some fun. You get the idea. The point is that there is a cost to each choice. Opportunity costs lie at the heart of this type of decision. Every choice you make means that you are not choosing an alternative. Every minute of your day could be used for something else.

Opportunity costs factor into nearly all business decisions. Just like you have to choose how to spend your time on the weekend, your leaders have to make decisions about how to allocate the team’s time and other limited resources. The leadership team is always weighing its options and trying to figure out how to maximize benefits and minimize costs for their choices. For most companies, this decision-making is primarily made on two criteria: time and money.

While this decision-making process is normally made on the fly, when the stakes are high, managers may turn to a more sophisticated method for examining alternatives and choosing between them. For example, consider how a company chooses to manage its facilities. If the company builds a new plant in Houston, it might be giving up the chance to update its distribution center in Tennessee. Losing out on one option is the opportunity cost of choosing the other.

You are probably most intuitively familiar with the concept of opportunity cost in terms of your household budget. Every dollar you spend means that you have one dollar less to use on something else. You give up everything else you could ever buy with that dollar. Only, for you, the choice is probably not just a financial one. You most likely weigh intangible factors like your job satisfaction and personal preferences much more heavily than a company does.

For example, what if you wanted to go to college? You obviously would think about the price of tuition. What else should you consider? You would probably look at your alternatives to spending four years of relative poverty while living in a dorm. Maybe you could get a job at a factory or as an apprentice in a trade and start earning money right away.

And if you do choose to go to college you still have to decide what your career will be. You have to choose between, let’s say, being a teacher or a lawyer. If it were strictly a financial decision, the choice would be clear. You would not give up a higher salary for a lower one. So why do some people choose lower paying careers? Because they include intangibles in their decision-making process. For some, the satisfaction they get from having their dream career offsets the opportunity cost of giving up a much higher salary in a profession that they don’t like.

At work, you probably have less control over decisions than you do at home. You might not, for example, be involved in making decisions about capital expenses (spending on the big ticket items needed to produce products and services). You will, however, probably have to choose where to best use your time.[1] Remember, every decision means you are giving something else up.

For example, if you are a salesperson, every day, you choose which clients to follow up with. Each one you contact means you are giving up a chance to talk to a different customer. The opportunity cost of the first client is losing the chance of a sale with someone else. Obviously, the goal is to keep your opportunity costs to a minimum.

This concept is particularly applicable at work when you have to choose how to spend your limited continuous improvement resources. You will seldom lack a long list of opportunities. Every time you select one project off the list, you are leaving the other ones undone. Those untouched projects are the opportunity costs of doing the project you chose. For that reason, it is a good idea to spend a chunk of time measuring the processes you want to work on so you know what the potential gains are. That way, you have a clearer idea of the opportunity costs.

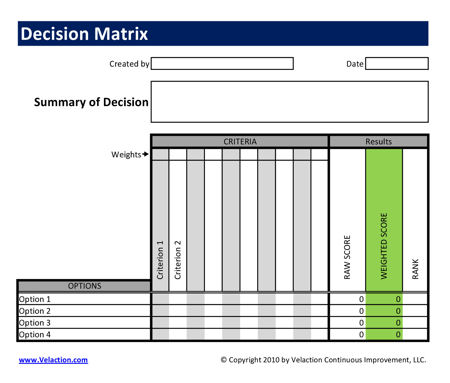

[1] Good decision-making skills will reduce the opportunity costs of your choices. Consider using the wide range of tools available to you, such as Pareto Charts and decision trees, to choose the best option.

![]()

We offer a short video about how to use our decision making template. It is a great tool to help you minimize your opportunity costs.

Pay careful attention to how you make your decisions. As competition increases, both between companies, and between employees, poor choices can cost you.

- The concept of value is relative. Let’s say that you and a friend each find a $5 bill on the street at the same time. You choose to go to the local coffee house and spring for a large, three-shot, extra foamy, non-fat, no whip, decaf, with room, white chocolate mocha. Your pal buys some bait to go fishing.

Since you don’t particularly care for standing along a cold stream for hours on end, you think you made a good choice. Your friend thinks that you shouldn’t take more than two words to get a jolt of caffeine, so he can’t quite understand your selection. If you apply your sense of value to his choice, you’d be way off on his opportunity cost. But he doesn’t think he lost out at all by choosing worms over coffee.

- Be careful about your audience. Companies primarily think in terms of money, and indirectly, in terms of time. They will look at the opportunity cost almost exclusively in terms of the “net present value” or the “payback period” of an alternative project. If you are pitching projects to a group of executives acting on behalf of the company, stick with the bottom line. Frontline employees, however, tend to value things differently than companies do. If you are trying to convince your coworker to join you in a project, think about what the opportunity will mean to her.

- Don’t forget about the cost of time. If you pull an engineer off her regular duties and put her on a kaizen team, there is a time cost to it. That engineer is not doing something else. One of her projects might have been to design a custom tool that is critical to launching a new product. If it is sitting on her desk, a new assembly line could be delayed as a result. The opportunity cost of bringing a group of people together can be immense.

- Opportunity costs require speculation. Because you never actually do the alternative you gave up, you can never be exactly sure of what would have happened. Perhaps that engineer learned something important during the kaizen week that led to a much better tool design once she was off the project. If she hadn’t had that assignment, her attempt at the tool may have failed miserably.

- Often, only part of the resources on two different choices overlap. Going back to the fishing example, the money is only part of the equation. Having a cup of coffee costs considerably less in terms of time than a day of fishing. Without the investment of several hours, the $5 of bait can be worthless. This apples-to-oranges comparison can be even trickier when you are factoring in things like job satisfaction.

- When you think of value, it should be after all the costs. If you were told you could make $2,000 on a side project, you would first want to know how much it would cost you (do you need to buy materials and tools?) and how long it would take. If it costs too much, there is no value there. So, what’s the problem? You often don’t know all the costs associated with the alternatives. Some costs are hidden and only come out much later.

Think about the cost of using a cheaper material in a product. The true costs might only become clear six months down the road when customers start complaining.

Don’t spend time second guessing decisions after the fact. It is easy to think things like, “We never should have done this project.” You quickly hurt your satisfaction with this line of thinking, since you don’t know for sure how the alternative would have gone. Just use the knowledge you gained from a decision that didn’t work out great to help your leaders make a better decision the next time around. Most often, this will involve helping them understand costs better.

Train yourself to think in terms of opportunity costs when selecting your improvement projects. Develop a system for how you make choices, and make sure that it includes two things: (1) several alternatives, and that (2) it considers the intangibles. A good way to do this is to use weighted criteria in making your decisions. This just means that you assign a rating and an importance to each factor—perhaps cost and impact on morale—and use a systematic approach for your decisions.

Key Points

- Make sure you are looking at the alternatives that you are giving up when you make a decision.

- Look at the full range of value, not just cost.

- Remember, value is relative. Make sure that you understand how others (especially your boss) are looking at the options.

![]()

Our decision making template helps you minimize your opportunity costs. If you choose the best option, given your criteria, it follows that you are minimizing the opportunity costs.

0 Comments